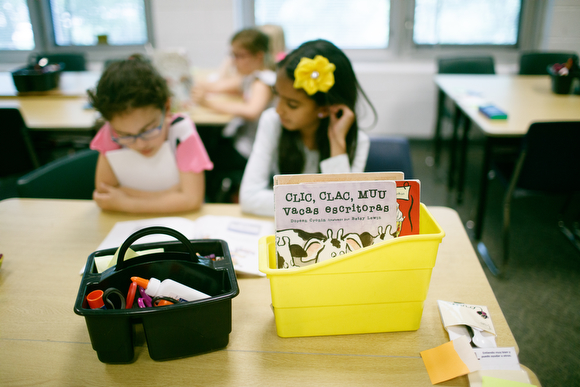

Cosette is a 5-year-old kindergartner who can be heard at home saying: “Can I read the libro?” and “Dónde está mi bike?” on a daily basis. At bedtime she reads a book out loud, like most children her age do, but it is written in Spanish. English books won’t be introduced to her until second grade. She is not growing up in a bilingual family, but she will most likely be proficient enough in Spanish to be considered bilingual when she graduates high school.

This young Grand Rapidian is part of an ever-growing movement in West Michigan called language immersion education. Students who participate in this type of program use the second language as a vehicle for learning the general curriculum. Think two birds, one stone…the same state mandated standards are met, but they are taught while being completely immersed in a second language. Students even take the same standardized tests (in English) as everyone else -- and typically end up outperforming their peers who are not in immersion programs.

The first immersion program in West Michigan debuted in the early 2000s; now there are 19 districts in the region that have total (classes taught using 100 percent Spanish) or dual immersion (50 percent Spanish, 50 percent English) programming offered beginning at the elementary level. Some districts in the area have expanded to include Mandarin Chinese dual immersion programming as well. Immersion education is offered within public, private and charter schools throughout the region, and in the majority of districts, a wait list has to be established annually for incoming kindergartners.

As parents are clamoring to get their children into these schools, it begs the questions: how did immersion education take root in West Michigan, and why does support continue to grow for it?

A changing world: Growing language options for students

Jesús Santillán sits comfortably in his office at Ada Vista Elementary after school and is full of excitement and pride. It’s no surprise, really; he’s in his element here at this flagship elementary. Ada Vista is considered a total immersion program and is one of the largest and most veteran in Michigan, servicing 1,000 students in kindergarten through 12th grade annually. Incoming kindergartners spend 100 percent of their day in Spanish. Not only do the classroom teachers speak Spanish, but complete immersion includes elective teachers, paraprofessionals, and librarians; even the school secretaries speak in the target language. That 100 percent is maintained through first grade. Between second and fourth grade English literacy is worked into the curriculum more frequently. At the junior high level the program shifts to a dual immersion model, in which only 50 percent of the students’ day is second language-based, and by high school students take two classes a day taught in Spanish, continuously building upon their kindergarten through sixth grade experience.

“In the beginning there was no Ada Vista; we began a Spanish immersion program at Ada Elementary with one pioneer class of 25 students,” Santillán says, explaining the history behind this development. “Our administration (the Forest Hills Public Schools) believed in us so much that they purchased our current building and began renovating it before we had enough students to fill it.”

Ada Vista opened as a kindergarten through sixth grade school and eventually outgrew itself again. It now functions as a kindergarten through fourth grade school, offering four classes per grade and a yearly waitlist of roughly 60 to 70 students. Santillán credits the increasing interest in Spanish immersion programming to the cognitive benefits students receive, the cultural awareness that is grown when you learn a second language, and becoming globally competitive as a result.

In Grand Rapids, dual language immersion options are also growing for students. Currently, the Southwest Community Campus

Ada Vista opened as a kindergarten through sixth grade school and eventually outgrew itself again. It now functions as a kindergarten through fourth grade school, offering four classes per grade and a yearly waitlist of roughly 60 to 70 students. Santillán credits the increasing interest in Spanish immersion programming to the cognitive benefits students receive, the cultural awareness that is grown when you learn a second language, and becoming globally competitive as a result.

In Grand Rapids, dual language immersion options are also growing for students. Currently, the Southwest Community Campus, which offers a Spanish-English dual language immersion program for about 840 students in kindergarten through eighth grade, is slated to expand. The recent $175 million bond that voters passed last November will allow the district to open a new Southwest Community Campus High School, giving students a dual immersion program through 12th grade.

Students at Southwest hail from throughout the city, and world, with many of the students having recently moved to Grand Rapids from such countries as Puerto Rico, Mexico and Guatemala, among many others. This means that in addition to helping native English speakers become fluent in Spanish, the program “gives our English Language Learners the opportunity to learn and keep their language,” says Southwest Principal Carmen Fernandez, who moved to Grand Rapids from Puerto Rico as a child.

Typically, the program starts with 50 percent of the students coming from each of the language groups -- so, 50 percent are native English speakers and 50 percent are native Spanish speakers (though that makeup can vary). In kindergarten and first grade, students spend 80 percent of their time learning and speaking in Spanish. That number changes to 70 percent Spanish in the second grade and 60 percent in third. In fourth through eighth grades, the students adopt a 50/50 dual immersion model.

“It gives our students a holistic view of the world,” Fernandez says of the immersion program. “Our vision is to produce bilingual, biliterate and bicultural students. Really, we’re producing multicultural students because we have so many different cultures here at Southwest Community Campus, and we celebrate all of them.

“I have discovered that a lot of students come in who are Hispanic, but they’ve lost that language – our program gives them an opportunity to feel proud of their culture, an opportunity to connect with their grandparents,” Fernandez continues.

‘The science of smart’: Why dual immersion students are outperforming their peers

The American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) agrees with Santillán that language learning is a more cognitive process, rather than a linguistic one, stating, “Studies have shown repeatedly that foreign language learning increases critical thinking skills, creativity, and flexibility in the minds of young children.” Santillán expands upon this, explaining how immersion education goes beyond the general foreign language curriculum and thereby drastically increases the cognitive benefits.

“Traditional foreign language classrooms function at the lowest level of cognitive development: students hear a foreign word and immediately translate it to English in their head; they receive lists of vocabulary and the English equivalents, making memorization a key factor to success,” he says.

In immersion education English is taken out of the equation, almost recreating the experience of learning their first language. New words are related to actions and visual objects only; there is no English word association. The brain is forced to function at a higher level and make connections it wouldn’t normally make. “In a true immersion experience children could all come into the classroom speaking a completely different first language and leave learning Spanish. English isn’t used as an acquisition tool in our school,” says Santillán.

American Radio Works, part of American Public Media, produced a radio documentary entitled,

“The Science of Smart,” in which they explored what language learning does to our brain. Researchers found that, “the act of juggling two languages strengthens the brain system that help people pay attention” -- something that has been reported time and again in

numerous scientific studies. They think this might be what leads to better academic performance in some children who grow up either bilingual or attend language immersion programs; students in dual language programs typically far outperform their peers in English-only classrooms.

Santillán agrees that immersion education helps students at Ada Vista learn how to troubleshoot and problem solve on their own at a young age. “When a student is learning addition they are not only focusing on that mathematical concept, they are considering the new vocabulary in Spanish associated with that concept and making connections between the new and old information; their brain is in overdrive and that builds valuable problem solving skills from the start,” he says.

Fernandez too stresses the skills and confidence that are built while learning another language.

“This is the New York of Grand Rapids Public Schools,” she says, “If you want a child to leave very confident and able to move through different avenues in life, then Southwest Community Campus is the place to be.”

Some parents have voiced concerns over standardized testing with immersion students. Because there isn’t a strong focus on English literacy right off the bat, they are worried their kids are put at a testing disadvantage. That couldn’t be further from the truth, says Sheryl Dalman, President of the West Michigan Alliance of Immersion Educators

Some parents have voiced concerns over standardized testing with immersion students. Because there isn’t a strong focus on English literacy right off the bat, they are worried their kids are put at a testing disadvantage. That couldn’t be further from the truth, says Sheryl Dalman, President of the West Michigan Alliance of Immersion Educators. As a school teacher at

Roguewood Elementary, a total immersion program, she has noticed that her students tend to score higher than normal on standardized tests. Santillán agrees that low test scores have never been an area of concern for Ada Vista, as does Fernandez.

"It's why a lot of students go on to Blandford and the Zoo School and City High School -- because of their grades," Fernandez says.

Education Week’s

Global Learning Blog found that English-proficient immersion students are capable of achieving as well as, and in some cases better than, non-immersion peers on standardized measures of reading and math. It is important to note when English is not introduced until grades two through five, there is evidence of a temporary gap in specific skills, such as spelling and word discrimination, but that within a year or two of studying English language arts that disappears.

Steve Faber, a parent of two sons who attend Southwest Community Campus, notes he too had concerns when his son started in the dual immersion program, but those worries quickly dissipated.

“That was my biggest concern: are they going to get that basic education; are they still going to know where Madagascar is, what the state capitols are, how to do math,” Faber says. “But they do. And my son, who’s in fourth grade, is reading and practicing mathematical concepts at an eighth grade level.”

A translation of worlds: How learning a language helps students to connect

Beyond the cognitive benefits of immersion, the cultural awareness and global readiness that occurs is a natural byproduct of this education model. “It’s not the language itself that makes the students culturally connected, but it opens up a door that wasn’t there before,” says Santillán. “When they notice that they are a little different now and realize that this additional language enables them to interact with people on a whole new level, they feel empowered and that’s huge. They want to connect with others, with those who are different than them; the motivation is real.”

Beth Dawson, a parent at NorthPointe Christian’s Spanish immersion program in Grand Rapids notices the same thing happening with her oldest daughter, who is currently in fourth grade. “The language program here has helped her expand her horizons more than we could have at home,” Dawson says. “Most of her teachers are native speakers; they bring their culture with them and use it as a tool in the classroom.”

Faber notes that many students in the classroom at Southwest hail from Spanish-speaking countries, which allows students from around the globe to form bonds with one another. This results in kids that are not only fluent in another language, but are able to build genuine empathy for people from other cultures, whether in their own city or around the world.

In an area where, like much of the U.S., the Hispanic population is the fastest growing community in the area (it has more than tripled in Kent County between 1990 and 2010, growing from a little less than 10,000 people in 1990 to nearly 30,000 individuals in 2010, according to the U.S. Census Bureau), those cross-cultural relationships are vital.

“My son really knows and understands kids from all over -- Guatemala, Puerto Rico, Mexico,” Faber says. “He understands where all of his friends come from and, because of that, understands more about our community, our neighborhoods, and our city.”

‘Our world is getting smaller’: Being able to compete globally

By 2020, individuals who are Hispanic are expected to account for half of the growth of the U.S. labor force, according to federal statistics, and globally it is considered the second most widely spoken language in the world. “Our world is getting smaller every day and something’s gotta give,” says Dalman. “We have to expand and enrich our learning model. Doing this opens up so many opportunities to compete globally.”

Santillán thinks immersion students have an additional competitive edge, aside from acquiring a second language. “Our students at Ada Vista are naturally more outgoing and willing to take chances,” says Santillán. Students in an immersion classroom are loud, they take a risk every time they speak in the target language, but they are all making mistakes together and learning from one another. “Students learn at an early age that it’s OK to take a risk and make a mistake; it’s OK to fail and try again. That’s an incredibly powerful lesson that most adults still grapple with,” says Santillán.

When asked if students with learning disabilities would benefit from this kind of a program, Santillán immediately says yes and supports his claim by saying, “students with learning disabilities can find real success in an immersion setting; our classrooms are more hands on and experiential than a traditional setting and this can be a welcome change for some students.” It’s important to note that acquiring a second language does come more naturally to some, just as some students are naturally more adept at math or science, but Santillán believes that with the right attitude and motivation, anyone can succeed.

In the future, the West Michigan Alliance of Immersion Educators wants to see a biliteracy seal given to immersion graduates across Michigan. “This seal would be a serious pat on the back for our students in Michigan,“ says Dalman. “Students would take the ACTFL standardized language proficiency exam and the criteria would be the same for all.” The ultimate goal is for students to receive college credits for their second language, much like an AP class. “They deserve recognition for all their hard work and dedication to the program,” says Dalman.

Ultimately, the end goal is to develop competent and successful global citizens. Becoming proficient in a second language is the first step, but immersion education is so much more than that. Every day is spent outside of your comfort zone; every day is full of risks, rewards and explorations. You leave an immersion school with the ability to speak a second language, but you also leave with an amazing skill set beyond language, simply because you decided to try.

Additional reporting contributed by Managing Editor Anna Gustafson.